How growth companies and startups should think about Cost of Capital

“I’ve never heard an intelligent cost of capital discussion”

Until not long ago, when equity or venture capital (VC) was the most important source of funding for growth companies and startups, cost of capital could almost exclusively be determined by the valuation of your company. The rule was simple: the higher the valuation, the lower the cost of capital (CoC).

In the past 2-10 years, depending on the geography you are looking at, the topic has gotten a lot more complex as more differentiated forms of funding have been introduced to the ecosystem. Not attempting a complete list of funding options, some noteworthy examples are:

- Venture debt (e.g., term loan)

- Revenue-Based Financing (RBF)

- Working capital funding

- Merchant cash advances

- Factoring

- …and even incumbent banks have selectively ventured more into the space of young and loss-making companies with traditional loans (although in most cases supported by public subsidies)

Therefore, it has become essential for entrepreneurs to consider more than just one form of funding and to think hard about which is the right one. Scrutinizing CoC is a very important aspect of those considerations, so we want to take a deeper look.

When thinking about fundraising, other relevant topics for consideration are non-monetary. For example, founders should evaluate loss of control (e.g., by transferring control to the board/shareholders), limitation of entrepreneurial freedom (e.g., through loan covenants), and assumption of risks (e.g., by granting collateral or guarantees). But I will leave that topic for another article.

To help the impatient reader, let me give you the conclusions from the following discussion about the cost of capital of startup funding in advance:

1.) Perceived CoC in the near future is probably very different from the actual CoC in the end -- in fact, in many cases what appears to be expensive [cheap] turns out be cheaper [more expensive] than the other option.

2.) Loss aversion bias has an impact on considerations of immediate cash-out versus potential future cash out – in fact, the final value of your equity (i.e, shares) will matter more for CoC than any cash-out on the way; this leads to frequent overestimation of CoC for debt funding, and underestimation of CoC for equity-based funding.

But before we start the discussion, a few general notes.

To reduce complexity, let's only look at equity (VC), venture debt, RBF, and the classic bank loan.

To reduce complexity even more, we will look at only 3 illustrative scenarios:

- Good scenario: your company experiences very strong growth and ends up being worth a lot.

- Mediocre scenario: things do not work quite as well as you imagined but, nevertheless, you manage to build a successful and growing business.

- Bad scenario: things do not work out at all.

And, since three time’s a charm, we will further reduce complexity by not considering the many stages, funding rounds, and situations a company can be in.

Let me also add that, for the purpose of this discussion, CoC will have the meaning of an actual 'loss of cash' as an absolute value at a certain point in time. For example, a classic bank loan has an immediate CoC (i.e., pay interest now), and VC has a deferred CoC, because you ultimately pay cash when you sell the company.

But now, let's finally get into it. I will show three graphs sketching the CoC development over time for the respective scenarios and briefly comment on what we see. (Within the graphs, VD is venture debt.)

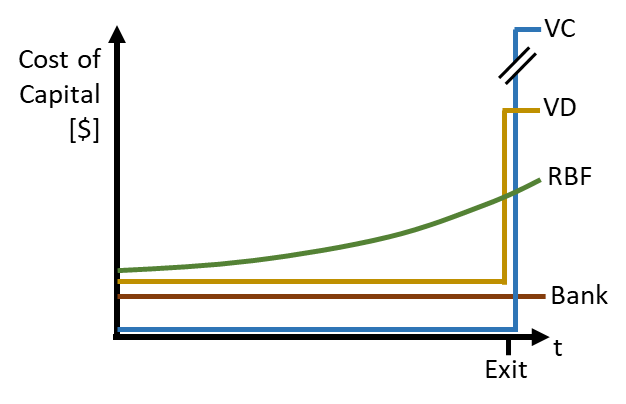

Good scenario:

Note: Chart is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect actual events.

- VC and venture debt investors get a share of exit proceeds, since they are shareholders or have other comparable arrangements (e.g., warrants) which let them participate in case of an exit.

- VC starts with zero CoC since there will be no immediate cash-out for the company. But in the end, it will have the highest CoC by far. In many cases, investors own more than 50% of the shares and get the respective share of exit proceeds. This is also reflected in VC's expected return on investment of >3x up to 10x or even more.

- That being said, VC has the advantage of being able to provide the biggest amount of capital independent of current financial performance which is important for high-growth companies.

- Venture debt’s CoC starts fairly low as the interest they collect is moderate in most cases. However, it will increase significantly in the end, because of equity kickers (e.g., warrants) which give the right to also participate in the proceeds of an exit.

- Sometimes other forms of debt funding (e.g., RBF) may also include a warrant, but only as an optional part of the deal. Venture debt, on the other hand, requires a warrant to make the return on investment attractive.

- RBF may start with the highest immediate CoC since it demands a cash repayment to the investor from day one in the form of a revenue share. But in the end, it ends up with a significantly lower CoC than VC, and in most cases also than venture debt, because RBF does not participate in an exit. In addition, total cash repayments to RBF investors are usually capped at 1.2x up to 2x (depending on the term of the loan) which is significantly lower than for VC.

- The bank has the lowest CoC in most cases because interest rates are usually moderate, remain constant, and banks do not demand any additional return. However, this is a rather theoretical observation, since young companies will usually not get any money from a bank as they are considered too risky, or founders may even have to accept personal liability. Nevertheless, I want to include banks in this discussion to give the full picture and increase general understanding.

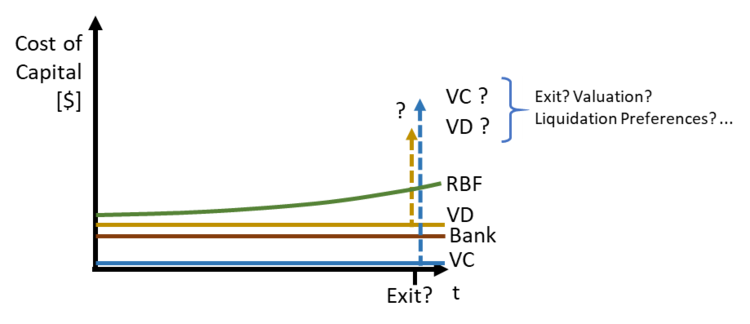

Mediocre scenario:

Note: Chart is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect actual events.

- Again, VC starts with zero CoC. Depending on the actual performance of the company, it can remain zero if, e.g., it turns out that the company can’t be sold at an attractive price, despite its performance. Alternatively, if an exit can be achieved, CoC will rise in the end according to the actual company valuation at the time of exit. Depending on the exit valuation, CoC can easily top all other form of funding.

- It is important to note, that the relative distribution of exit proceeds, i.e., the relative CoC can play an important role. If your VC funding includes Liquidation Preferences a very big chunk (or maybe all) of the proceeds from a smaller exit might go to investors. In this case, the absolute CoC could be low because of the low exit valuation, but the relative CoC is very high because most of it is going to the VC.

- Even more severe could be a scenario in which the entrepreneur wants to sell the company, but the VC blocks the exit because her implied return on investment would not meet her standard (and vice versa).

- For venture debt the same is true as for VC: Because of its right to participate in case of an exit, CoC can easily overtake bank and RBF, depending on the exit valuation.

- The Bank (again, a theoretical observation), venture debt, and RBF start and remain pretty similar.

- RBF might, in many cases, have slightly higher CoC which rises over time, since its revenue share model makes it participate in growing revenues.

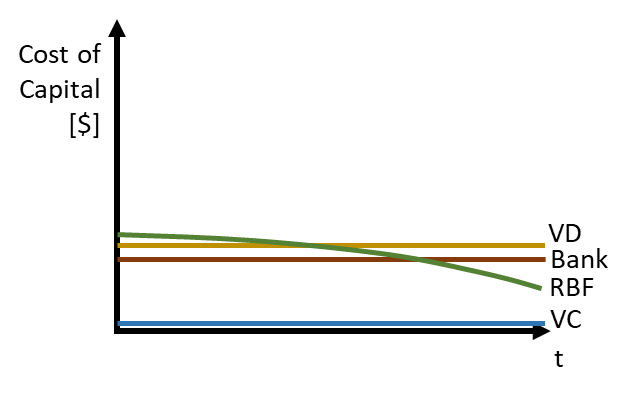

Bad scenario:

Note: Chart is for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect actual events.

- VC is the same as in the Mediocre scenario but without the potential of an increase in the end. In a bad case scenario, shares will not be worth much and, hence, CoC will practically remain zero.

- Bank, venture debt, and RBF start pretty similar, again. Bank and venture debt remain flat over time due to the classic interest payment they usually require.

- RBF's CoC would also remain flat or, if things go south, even fall over time. Payments to the RBF investor mimic the development of revenues, as RBF demands only a share of revenues.

Please also note that it often makes sense to mix different forms of funding in one funding round. Especially VC and RBF or VC and venture debt go well together. VC and RBF, for example, has the advantage of combining a high total investment amount with reduced dilution and loss of control.

Soon, we will follow up with an additional article discussing concrete examples to help calculate your individual CoC scenario.

Again, I hope you appreciate the many simplifications in this discussion. As always, idealized scenarios do not really fit any actual company in the world. My intention was to give a brief introduction on cost of capital considerations for growth companies and startups to provide some food for thought for your next funding round.

I hope I achieved at least that :-)

If you want to learn more about RBF in general, please have a look at our Primer on Revenue-Based Financing here.

The analyses and conclusions contained in this article include certain statements, assumptions, estimates, and projections that reflect anticipated results and have been included solely for illustrative and informational purposes and do not reflect actual events. This is not an offer or sale of, or a solicitation to any person to buy, any security or investment product or investment advice.

We love meeting new software companies, so let's talk.